From Studio | Brainripples

Happy New Year! Честита Нова Година!

Greetings of the New Year!

My literary and language adventures for 2020 include learning Bulgarian.

My goals:

- learn enough Bulgarian to be able to easily navigate Bulgarian grocery stores and read / request what I need without English.

- start reading Bulgarian stories and poetry.

I’ll try to remember to check in later this year to give you a peek at my progress.

And now…

As you have found your way to me,

Three gifts for your 2020!

A new place for inspiration and author connections

Visit my good friend Gemma L. Brook, torchbearer of stories and storytellers, who shares new publications and spotlights new authors.

Warm wishes for good health

I failed to mail my holiday cards these past two years, but I have never forgotten you. Yes you, sweet stranger. Yes you, my family. Yes you, dear friend with whom I have not spoken in so long! To you all – I wish you the best of health, happiness, inspiration, and prosperity in the year ahead.

2012 Throwback

Since the Wild River Review is now offline, here’s a republish of the original essay, “Our First Language: Why Kids Need Poetry”.

I’ve replaced deadlinks with comparable compass points to help you connect with the inspirations for this discussion.

*

Our First Language: Why Kids Need Poetry

I believe poetry belongs in every kid’s backpack. Poetry came to me through stories read by my parents at night, songs learned on the playground, and my first grade teacher, whose poetry curriculum was also a primer in paying attention and speaking with purpose.

For me poetry is akin to my favorite garden shovel: always on hand for fun and difficult work alike. I use poetry to dig through questions. On October 31, 2011 our world population passed 7 billion, and United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon posed us these worthy queries:

What kind of world has baby 7 billion been born into? What kind of world do we want for our children in the future?

When I consider how we will learn to share justice and prosperity among even a fraction of our 7 billion voices, I can only conclude that we must first learn to do the work of poetry. By sharing poems with kids from alphabets onward, we equip them with critical tools for twenty-first century cooperation.

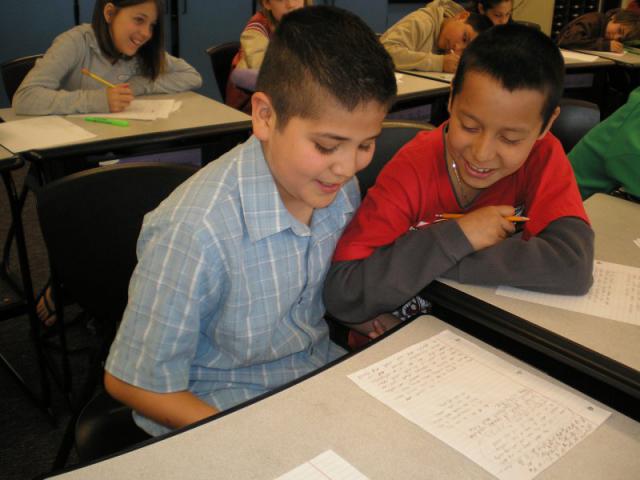

Poets in Schools, Pair of young writing students smiling while reading. Photo courtesy of the Skagit River Poetry Project.

Poetry is practice in communication basics like curiosity, attentiveness, patience, confidence, and empathy. To interpret poetry, we must cultivate a curiosity for the experiences of other people, attend carefully to each word, have the patience to read through repetition and ego, maintain the confidence to be honest in our responses, and use our empathy to allow each poet’s words and experiences to broaden our world perspective.

These same communication skills enable us to cooperate and work together in groups. Cooperation requires every person to have a say in the decisions that affect their livelihood. When someone speaks, we must be an attentive audience to hear beyond what is spoken. So what do we do when a conversation turns bitter, or data gets confusing, or people start to behave badly? As with poetry, when something is unclear or uncomfortable we must learn to look again, listen closer, embrace uncertainty.

Few kids may plan for cooperative work with fellows, but most kids like to play and have fun. Poet and nurse-midwife Rebecca Frevert muses:

I believe that poetry is our first language; we hear it from birth in the rhythms of ditties and lullabies as our parents soothed us to sleep. I’ve wondered why we lose this love of language as we grow up, becoming intimidated and put off whenever the word “poetry” is attached to a reading.

My educated guess is that kids will not embrace poetry when the practice is not fun. An early start may also be a key to lifelong poetry appreciation. Frevert read poems to her sons from a young age, and she admires how they read and write poems as adults. “I feel that if elementary level teachers performed poetry for the students, it would catch hold and stick,” she says. “For our family, the Youth Speaks program in Seattle with poetry performances at the Moore Theatre were a great influence.”

In 2009 Frevert began to extend poetry to her community in Everett, Washington with a poetry kiosk. She explains how when life gave her a dirt pile, neighbors grabbed shovels and made daffodils:

Years ago, after a load of compost dumped on the parking strip burnt the grass to death, my seventy-year-old neighbor Emory and I dug up the sod and planted a flower bed. He’s left earth now, but I’ve always called this little garden Emory’s Bed. A perfect spot to catch the eye of the walkers who might stop a few minutes to read a poem. The poetry stand is a simple design painted blue with a Plexiglas lid that keeps out the rain (but not the spiders who love to leave cocoons in its corners).

Neighborhood Poetry Kiosk in the Garden. Photo courtesy of poet Rebecca Frevert.

Her sign encourages passersby to read poems and contribute. When the Frevert family’s beloved dog Sunny passed away in 2009, one of her sons placed a poem about death and loss in the kiosk. Neighbors replied over several days with flowers and notes of sympathy. In 2011, a young poet named Devany (now 10 years old) shared three of her own handwritten poems in the kiosk, including this one:

My aunt

She has lots of

Tattoos

She really likes blue

She has a baby

It drives me crazy

But she says love makes a true lady.

Frevert’s kiosk visitors demonstrate the communal nature of poetry, and remind us that poems are shared person to person through language and breath. Poet Robert Pinsky elaborates:

The medium of poetry is the human body: the column of air inside the chest, shaped into signifying sounds in the larynx and the mouth. In this sense, poetry is as physical or bodily an art as dancing … in poetry, the medium is the audience’s body … The reader’s breath and hearing embody the poet’s words. This makes the art physical, intimate, vocal, and individual.

Poems are “intimate…individual” conversations that we can use to share ideas, gain audience, and discuss challenging subjects. By teaching kids to experiment with words, we can prepare them for the hard work of adult problem solving.

Poets in Schools, Kurtis Lamkin with writing students. Photo courtesy of the Skagit River Poetry Project.

University of Cambridge Professor of Children’s Poetry Morag Styles makes the case for children’s poetry. In addition to didactic and popular children’s poems, she celebrates perhaps the most sacred of all kid poetry—ridiculous songs that kids create with each other. Styles shares a few rhymes from the Scotland playgrounds:

Man United are short-sighted

tra la la la la la la la la

They wear rubies on their boobies

tra la la la la la la la la……

She goes on to quote 2010 T.S. Eliot prizewinner Philip Gross, who suggests: “children imbibe poetry from people who bring to it some ease and passion … young people can be bold readers of rich and demanding poetry – and writers of it too – when they come to it as participants, rather than as passive consumers.”

A new national curriculum released by the British Department for Education may help nurture the next generation of poetry participants. Under the proposed curriculum first year students would focus on phonetics, while second year students would be expected to hear and discuss classic and contemporary poetry, be familiar with a range of stories, fables, and literary language, and be capable of reciting poetry with appropriate intonation to make the meaning clear.

My adult-poet self says, “Awesome! Way to bring home the poetry, Secretary Gove.” However, my inner perpetual teenage-poet self says, “Curriculum, phonetics, intonation? Yawn. Can’t breathe with all this hot air!” Kids know that the proper order of operations is play first, then work.

During his time as US Poet Laureate, Billy Collins hosted the Poetry 180 Project at the Library of Congress to help American high school teachers and students have fun with poetry. Useful resources like “How to Read a Poem Out Loud,” accompany 180 handpicked poems. Collins uses his own “Introduction to Poetry” for Poem #1, which describes an attempt to share a poem with students. Instead of heeding his guidance to carefully consider the poem, students “begin beating it with a hose / to find out what it really means.”

Poets in Schools, Elizabeth Austen with writing students. Photo courtesy of the Skagit River Poetry Project.

A quick online search for “why do people hate poetry?” or “poetry sucks” retrieves hundreds of articulate poetry students (and teachers) who describe feelings of expectation and disappointment when they approach a poem, think poems sound absorbed with distant and unknown language, or feel like poems are written as private and unsolvable mysteries. These honest writers call out what many people think: “I totally don’t get this, and I have no idea where to start.”

I often get the “where to start?” feeling when I read too much news. Poet Naomi Shihab Nye describes how we can use poetry to gain perspective on difficult situations:

… I do think that all of us think in poems. I think of a poem as being deeper than headline news. You know how they talk about breaking news all the time. Too much breaking news; trying to absorb all the breaking news, you start feeling really broken. And you need something that takes you to a place that’s a little more timeless, that kind of gives you a place to stand, to look out at all these things. Otherwise you just feel assaulted by all the tragedy in the world.

Before donning the weight of all the tragedy in the world, some kids can be overwhelmed by personal hardships. Founded in 1992 by Richard Gold, the Pongo Publishing Teen Writing Project is a nonprofit volunteer effort to help kids in distress express themselves through poetry. Pongo reaches out to children and young adults who are in jail, on the streets, or in other ways leading difficult lives. By sharing poetry with kids in a safe environment, Pongo participants learn to discuss losses and traumas like the death of a parent, abandonment, neglect, abuse, rape, addiction, or a parent’s addiction. In a recent blog post, Gold writes:

I’ve seen that life’s worst experiences can exist as strangers in us, separate, like people we don’t know and don’t want to know … I’ve seen that our emotions after life’s worst experiences can be sealed in a variety of containers, some buried, or in a black hole, some that explode unexpectedly … But I’ve also seen that through poetry, people can open these containers, and move their contents, these painful emotions, into new frames that are more open and repurposed for a meaningful life.

The poem that follows Gold’s remarks is entitled, “Poetry Saved My Life” by Bad One, a young woman, age 14. Bad One’s poem describes how she chooses poetry, rather than violence, as her path to resolution. Why does poetry work for Bad One? Perhaps it is the warm Pongo welcome:

You don’t have to be an experienced writer to create Pongo poetry. We appreciate the importance of what you have to say. Honesty is the quality we value most.

Pongo makes poetry accessible if not through jubilation, then at least through honesty and direct speech. With their open approach, Pongo uses poetry like a discussion table of unlimited seating capacity, where the most sensitive subjects are open for everyone’s respectful consideration.

In Yemen, poetry is an essential mode of community and political discourse within rural areas and among metropolises. The introduction to Johanne Haaber Ihle’s documentary “Men of Words” states, “In the context of illiteracy and censorship, current problems are discussed through the ancient tradition of poetry.” Programs like Literacy Through Poetry (LTPP) use poetry and oral traditions to teach Yemeni girls and women how to read without formal education. Dr. Najwa Adra explains:

Using women’s poetic expression serves not only to promote literacy, but to preserve a valued and valuable tradition as well. In Yemen, short, two line poems are utilized effectively to mediate conflict. Poetry synthesizes the issue at hand and allows for disagreement without confrontation. When someone feels insulted, expressing anger in a poem is more sophisticated than physical violence or shouting. Moreover, rhetoric that one’s adversaries appreciate increases their willingness to accept compromise. This is critical thinking at its best.

Folk poetry is also a centuries-old oral tradition in poet Kristiina Ehin’s home of Estonia. In an interview with The Bitter Oleander, Ehin describes her delight at how quickly children can adopt the traditional regilaul—runo song. These rhythmic narratives tell amazing, sometimes frightening stories with themes that preserve layers of unwritten cultural laws:

Yesterday I sang regilaul to the children at the seashore. To my surprise they listened in fascination and sang along … if you explain the dialect and archaic words a little, then children can find it very interesting. Going to bed in the evening, five-year-old Emma started singing to those tunes, making up her own words. She sang a long regilaul … it was very special to hear how easily a child had acquired the metre and poetics of this form and how easily she improvised in it.

Ehin goes on in her interview to articulate the tasks of the poet:

How can I find common ground with my listeners, and introduce my poems in such a way that even themes that might seem strange to some are nevertheless interesting to them?

These are the tasks for all of us: to listen to each other for subtle common ground, to speak with thoughtful honesty, to visualize and experiment. The collective needs and messes of 7 billion people demand the slow, creative work of cooperation among neighbors as well as nations.

Without tools like poetry to move us beyond fear, our ability to think clearly and creatively will suffer. Poetry empowers us to meet the “where to start?” feeling with curiosity, attentiveness, patience, confidence, and empathy. If we want to acknowledge old ways that do not serve prosperity, move on toward a more just and equitable future for everyone, let us teach our children to play with poetry.

Please join our conversation with a link to a favorite poem, or a fun idea for teaching poetry for kids. To enjoy weekly poetry discourse I recommend the PoetsWest broadcast on KSER community radio every Thursday at 6:30pm Pacific Time. When in doubt, pop a poem in your pocket and share it with someone you meet.

Photos of Poets in Schools courtesy of the Skagit River Poetry Project in La Conner, Washington.

Photo of Poetry Kiosk and Devany’s poem courtesy of Rebecca Frevert

The author wishes to acknowledge the generous contributions and enthusiastic support provided to her by:

— Director Molly McNulty, Linda Talman, and staff at the Skagit River Poetry Project

— Washington State Poet Laureate (2012-2014) Kathleen Flenniken

— Washington poet and nurse-midwife Rebecca Frevert

— Pennsylvania author Gerri George

Hear me talk shop with S. Evan Townsend on the Speculative Fiction Cantina

I had the pleasure of representing Running Wild Press on the Speculative Fiction Cantina podcast this September, chatting with podcaster and fellow author and Washingtonian S. Evan Townsend, as well as fellow author and marketer Rick Karlsruher. (Yes, the description says Lisa Diane Kastner – she’s my rockstar co-founder at the press.)

The Speculative Fiction Cantina with Jade Leone Blackwater and Rick Karlsruher by Writestream Radio Network

Grab your speaker (or your headphones) and a task that needs doing, and let our conversation carry you away.

Thanks so much Evan and Rick!!

Feature Writer Interview: Journeying with Madhu Bazaz Wangu

If you are looking for some New Year’s inspiration, read our interview with Madhu Bazaz Wangu—author, artist and founder of the Mindful Writers Group.

For 20 years Madhu taught Hindu and Buddhist art history at the University of Pittsburgh, Rhode Island College and Wheaton College, Massachusetts. Today she teaches writers from novice to professional to meditate, collaborate, and improve their work.

*INTERVIEW SPECIAL* LIMITED TIME BOOK DISCOUNTS END MONDAY JANUARY 23, 2017

New Year, New Book, Great Deals!

For our initial interview days only: get a great deal when you buy Madhu’s debut novel The Immigrant Wife: Her Spiritual Journey, available in print and ebook at Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

For our initial interview days only: get a great deal when you buy Madhu’s debut novel The Immigrant Wife: Her Spiritual Journey, available in print and ebook at Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Special eBook Prices:

- $2.99 – Thursday thru Sunday, January 22nd

- $0.99 – Monday, January 23rd only

I suggest you go get your copy (and maybe one for a friend too) and then come right back—we’ll be here, promise.

*

JLB – Greetings Madhu, and thank you for joining us at Brainripples for an interview. I’ve been interested in your work since we first met through Pennwriters, and I’m thrilled for the chance learn more about you now that I’ve read The Immigrant Wife: Her Spiritual Journey. Your credentials are vast—artist, author, scholar, teacher, traveler—tell me a bit about your creative origins. What were your first media as a child? What attracted you to spiritual and historical investigation?

MBW – Thank you for inviting me!

From my early teenage years my father, a humanist, encouraged me in my attempts to paint and write. My mother, a compassionate and generous woman, enjoyed art and was not particularly religious. A voracious reader, my father took me to library every month to borrow eight books, maximum allowed. We regularly went to art exhibitions, watched theatre and attended musical recitals.

I graduated in Painting and for my Masters studied Art History and Criticism. I was more interested in why and what than how of art. Whereas the academic requirements emphasized cultural context and formal analysis of art, I was interested in its content. Both Indian as well as European art history were replete with religious subject matters. I had not read scriptures so did not know much about religions except by cultural osmosis. Before I could fully appreciate historical works of art I needed to know Buddhist, Hindu, Islamic and Christian myths, symbols and rituals. Thus began my quest for knowledge of the world religions. I had no concept of spirituality at this stage.

JLB – Tell me a bit about your Mindful Writers Groups. How do these groups work? What kinds of writers typically participate?

Tibetan Prayer Wheels, Lhasa

MBW – Fast forward to 2010. I had been meditating for twenty years. The practice of mindful meditation honed my focus and motivated me as a writer. After a meditation session my writing flow was always smooth, my concentration sharp, intuitive ideas and insights related to my work floated up into my mind more often. This was magical! The days I did not meditate I found my creative flow blocked and my focus diminished. I wanted to share this experience with as many fellow writers as I could.

So I wrote four meditations and recorded them in a CD, Meditations for Mindful Writers: Body, Heart, Mind. Master meditators consider body as the basic portal that yokes us to the creative and spiritual source within. Listening to the CD as you sit still and breathe connects you to the body and eventually your creative self, normally dormant within each one of us.

For the first meeting of the Mindful Writers Group I booked a room at Eat’n Park in Wexford, (North of Pittsburgh, PA) and posted an invitation in Pennwriters newsletter. Five writers showed interest. I recited the body meditation for fifteen minutes (the CD had not been made yet), wrote in our journals for fifteen minutes and wrote for two hours. Now the writing time has been extended to four hours but we use different meditations from the same CD. The writers’ experience ranged from being a novice to professional.

The Wexford group is thriving under Lori Jones‘ leadership. Now we have twenty members and a waiting list. Last year I started another Mindful Writers Group at Waterworks Mall, (East of Pittsburgh, PA). Currently the group has thirteen members.

My second CD, Meditations for Mindful Writers II: Sensations, Feelings, Thoughts is forthcoming.

I am also planning a Mindful Writers Group via Skype for January 2018. To get on the waiting list simply email me at: madhu.wangu [at] me.com

Each year, the Mindful Writers Group meets at two retreats organized by Kathleen Shoop and Larry Schardt. Productive, serene and filled with warmth of fellowship of creative minds, they are the most magical retreats I’ve ever attended.

JLB – What have you learned from holding these workshops? Want to share any tips for success for workshop organizers?

MBW – I learnt when writers meditate and write together the atmosphere turns ethereal. Everyone is so focused within, pouring out feelings and thoughts in words that the creative energy emanates from their presence. The energy fills the room.

I learnt that there is dearth of opportunities for writers to write together. Writers spend most of their lives in isolation. They crave for such opportunities. Meditating together not only sharpens focus but also enhances camaraderie.

To start a similar workshop. You need a group of writers who are genuinely interested in improving their writing skills and enriching their lives. Once or twice a week meditate, journal and write together. You’ll get addicted to this meditation practice.

JLB – I’ve wanted to read your books for years, but it was finally The Immigrant Wife—your most recent work—that I picked up first. I enjoyed how your book covers the evolutions of womanhood, artisthood, marriage and parenthood, affirms the experiences of family, world travel and immigration, all while educating readers in history, culture, spirituality, and religion. Can you tell me about some of the inspirational roots of this story? How much of Shanti’s travels are based on places you’ve visited?

Old Shanghai Market, Nanjing Road

MBW – Thank you for reading, The Immigrant Wife! It is my debut novel and rooted in my life as an artist, art history professor, my travels around the world and my love of nature and cooking. Shanti’s world voyage is based on my travels to Bahamas, Venezuela, South Africa, Kenya, India, China, Japan and Philippines.

JLB – Your main character Shanti explores her artistic craft and instinct with a variety of media throughout her life, especially painting. I like how your prose paints scenes and moods with careful brush strokes, as portraits crafted to evoke each of the reader’s senses. Can you talk a bit about your methods as a wordsmith and visual artist?

MBW – Before I learned to write professionally I was an artist. Most of my oil paintings were landscapes and portraits. I used models for portraits and sketched outdoors when a landscape touched my heart/mind. Then I painted the landscape at home. In either case each painting told a story. I have had several one-person shows. As a professional writer I craved something deeper. I did not know why. In 1981 when I got an opportunity to study I decided to do my doctorate in Phenomenology of Religion. I immersed myself in the study of world religions with emphasis on the why of the field. For writing books about history of religions my emphasis was on thorough research and methodology.

For fiction, I don’t start writing until a topic hits me hard. When it does I absorb it and mull over it for months if not years. When I feel an inner urge to write it down I pour out my heart in words, spontaneously and uncensored. One of the best ways to do this is to join NaNoWriMo. At this website I wrote the first drafts of three novels during three different years.

I read and revise the first draft until it feels ready for a concept editor. I rewrite parts of the draft and revise based on her recommendations. Then is the time to give the draft to read to a trusted writer friend or someone who reads a lot. In my case that person is my husband, a voracious reader. I incorporate his suggestions and mail copies of the next draft to my first circle of readers. They are my writer friends whom I trust. Their suggestions incite new ideas and help me dig deeper to improve narration, characters, settings and dialogue. After yet another revision (fourth or fifth by now), I ready the draft for the line editor. Based on line editor’s comments I read and revise my novel as if it was someone else’s work. The final draft is ready. It goes to a proof-reader. And the writing stage of the book is done.

Moon Door, Yu Garden of Happiness

JLB – I understand you wrote and edited this book over several years. How did you approach the initial drafts – on a steady schedule, or in chunks as your time allowed? Did you map out the whole story first, or did you let Shanti take you where she wanted to go?

MBW –The Immigrant Wife started as a novella and remained in my desk drawer for years. During one hundred days of my travel around the world I kept a journal. The journal started as the record of my thoughts, feelings and observations about the countries and their people. Slowly my written observations turned deeper. I was enticed, forced to look deep inside myself. I was not aware of this at that time and only realized it when I reread the journal.

My husband suggested that I combine the novella and the journal and turn it into a novel. And voilà the first draft of The Immigrant Wife was born! Some parts were deliberately written but many others parts wrote themselves, surprising even me.

JLB – What advice would you give authors for how to select the right editors?

JLB – What advice would you give authors for how to select the right editors?

MBW – Word of mouth is the best way to learn about agents and editors in your genre. Of course, editor/agent guides are good too. I tried out several editors before building up relationships with the ones that I felt comfortable with. Some of my editors are the ones who I started working with Chance Meetings, my first collection of stories.

JLB – Shanti’s husband Satyavan is both a tormented and tormenting character. What were your greatest challenges in writing this character?

MBW – In my novella Satyavan was an average male chauvinist. He behaved with Shanti the way I have observed many men behave with their wives without even realizing it. But I had to give him a nerve-racking reason to be the way he was. So I gave him a cause to torment about. With his pain-body he was bound to torment his wife as well. A news item about an infant abandoned at a junk-pile in Chennai, India gave me the idea of the cause.

JLB – Shanti’s strength and intuition often waiver in very human ways. What were your challenges in bringing Shanti’s noble spirit down to earth, to make her relatable and flawed like the rest of us?

MBW – Great question! In several earlier drafts Shanti was too good to be true. She seemed flawless and thus irritating. While revising several drafts I either rewrote some of the parts about her know-all attitude, universalized some others making her wise instead, and deleted a few parts. That added to be about thirty pages. And it worked.

JLB – Would you tell us about your experiences in publishing? What were some of your top challenges? Top successes? What are your preferences today when it comes to self-publishing or indie publishing?

MBW – My non-fiction books were traditionally published. Having finalized the manuscript of The Immigrant Wife: Her Spiritual Journey I mailed sixty plus queries. I received forty form rejections, some gentle rejections and five replies with suggestions that I actually used. Yet, the rejections had dispirited me. I kept the manuscript in my desk drawer and decided to write my next book.

A good friend, Kathleen Shoop, an award winning best-selling author, had read my fiction. Even before I had sent out query letters to agents she had asked me to self-publish. After hearing about the rejection letters she coaxed me to self-publish. She said it was my responsibility as a writer to reach my readers. I was persuaded. And here it is!

Jin Mao Tower, Shanghai

JLB – I understand you recently visited China and Tibet. Would you tell us about your trip? What was the most delicious part of this trip? What was your favorite new learning?

MBW – Like all the previous trips our recent trip to China and Tibet taught me that when you leave home and travel mindfully in an unknown land it is also a journey within. More I expand my outer experiences more I seem to broaden and nourish my Self.

In China and Tibet the first thing that struck us was the juxtaposition of modernity with tradition. High rise buildings contrasted with historic sites. We visited Forbidden City, Tiananmen Square, The Great Wall, Chengdu Panda Park and Warrior Tomb Museum and met people on the way. We realized how much better world would be if it was possible for all of us to personally be in a country and meet its people.

In Tibet, we saw Dalai Lama’s Potala Palace and Buddhist monasteries on Lhasa’s high mountain peaks. We marveled at their architecture and beauty and we shopped at old Lhasa market. A feeling of warmth still envelops me as I write this.

Warrior Tomb Museum, Shaanxi

JLB – What are some of your favorite places that you’ve visited around the world? What places are on your wish list for future travels?

MBW – Within US, Alaska—paradise on earth; outside US the choice is difficult. Each country has its unique beauty; if seen from the heart’s eye every culture is a fantastic adventure. My favorite tends to be the most recent country I have visited. This year we plan to go to the Caribbean islands in Spring and Japan in Fall.

JLB – Can you tell us about any of your upcoming work? What themes and questions most attract you at the moment?

MBW – The manuscript of my second novel, The Last Suttee is currently with my writer friends. Suttee is an ancient Indian ritual in which a widow self-immolates on her dead husband’s burning pyre. The ritual was banned a century ego and declared criminal act since 1987 but in some remote villages it is still glorified.

One such suttee ritual took place in 1987 that unsettled my mind and heart. That year I decided to write a book about the unfortunate event. Only recently was I able to actualize that event in the novel. Kumud, the protagonist of the novel witnesses a suttee as a nine-year old. It’s memory torments and haunts her until she gets an opportunity to save a sixteen-year-old, whose husband is on his death bed. She wants to commit suttee. But it becomes Kumud’s quest to save the girl from herself.

JLB – Before I let you go, my favorite last question: what words of wisdom can you share for authors and artists who want to create polished, passionate work?

MBW – What topic do you feel passionate about? How do you feel in your body when you think about the topic? Spontaneously and freely write about it. Don’t worry about grammar, sentence structure or words. Just pour your heart out. Then read it. You’ll find many burning coals under the heap of your words. They will keep your passion warm, help you keep going. Make an outline of a story or an essay using those pieces. Reread it. Revise it. Rewrite a sentence, choose a better word, revise dialogue if these do not feel right. Story characters will begin speaking to you.

MBW – What topic do you feel passionate about? How do you feel in your body when you think about the topic? Spontaneously and freely write about it. Don’t worry about grammar, sentence structure or words. Just pour your heart out. Then read it. You’ll find many burning coals under the heap of your words. They will keep your passion warm, help you keep going. Make an outline of a story or an essay using those pieces. Reread it. Revise it. Rewrite a sentence, choose a better word, revise dialogue if these do not feel right. Story characters will begin speaking to you.

If you get stuck go for a walk in nature, meditate or do a repetitive task such as knitting, gardening, cooking. Individualized tools that help you hone your craft will surface. They are dormant inside you.

Think with your whole self, body, heart and mind, not just with your head. Your whole self thinks better than your brain alone.

*

Madhu, thank you again for kicking off our New Year at Brainripples and telling us about yourself, your journeys, and your methods.

Jade Buddha Temple, Shanghai

Images appearing in this article are used by permission of Madhu Bazaz Wangu. Do not reproduce without permission of the artist.